CLA PRACTICE SPECIAL

A Short Journey Exploring the Application of the CLA to Fencing Coaching

INTRODUCTION

How do coaches make decisions? What do we base our decisions on? How do we know they are good decisions? What are the alternatives, why are some rejected over others? Where can I find information to help make better decisions?

Decision making based on experience alone will get us so far. If we accept that doing things the way we’ve always done them is unlikey to give us different outcomes, then there is a need to keep our decision making up to date, to develop critical thinking and become reflective practitioners. When we do that, we come to realise that theory-informed practice is not only a powerful tool for decision making, but it also opens the door to creativity and innovation.

The relationship between theory and practice is a dynamic one - one can’t work without the other - and understanding the healthy tension that exists between them is key to making informed coaching decisions. Einstein expressed it thus:

"In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice they are not."

That’s not to say that we should coach with a book in one hand and a sword in the other, more a matter of seeing coaching as an act of professional judgement and decision making (PJDM), of continuous professional knowledge development to complement our experiential learning. If coaching is ever to be considered a profession, then we should strive to make decisions on a professional basis. If you don’t agree with that, don’t worry, it won’t change my mind about going to a qualified and experienced dentist to have my teeth looked after!

"There is nothing so practical as a good theory" (Kurt Lewin)

When it comes to deciding on a particular coaching intervention, we find that all coaching decisions are about how to constrain practice. That is what coaches do. You cannot coach without using constraints, because a constraint is anything that is guiding action.

“All coaching is constraints based coaching. All coaching involves the manipulation of constraints.” Rob Gray

Every time the coach walks into the Salle, they are affecting behaviour; when they put their blade in front of a student, they are inviting movement; when they instruct or demonstrate to do it a particular way, they are constraining choices; every type of practice - blocked, random or variable; whether we use bodyweight or the weights room and how we warm up; these are all examples of constraints. How we make decisions about any coaching session involves decisions about what constraints in the fencer, task and environment we want to manipulate.

The CLA is a framework designed to help us make decisions about how to manage constraints in a particular way, based on solid science, research and evidence. The CLA Fencing Coach is one who is guided by a contemporary view of perception and learning - two enormous areas of academic study that can be quite overwhelming to take on. I think the simplest way of understanding it is to become familiar with three basic concepts that render CLA coaching quite different to how we were taught.

Direct Perception: We move to perceive and perceive to move without the need for additional processing or breaking actions into component parts. We naturally learn to move by tuning our perception-actions into the environment.

Self-organisation: Complex systems like human beings, rivers and cloud formations evolve and adapt to the forces being applied to and constraining them.

Emergent learning: Learning is non-linear and development is unique to the way each of us interact with the environment.

Taking this alternative approach, it transpires that there is no need to teach and repeat technical fundamentals to the point of automaticity. Instead we can manage their new and emerging relationship with the environment holistically and organically, to guide them as they learn to function and adapt to the sport in their own way. Sounds like total Jedi-speak, right? It did to me too, but when I started to look at what underpinned the decision making of world class coaches, I kept coming back to the CLA and when I started to put it into practice, I was startled by the results.

PRACTICE NOTES

I’ve been asked for some time now to give examples of the CLA in action. The idea fills me with dread. I’m not even sure if it is possible. Why do I feel this way? Well, because the CLA is a theoretical framework and I can’t demonstrate a framework or a theory. I can show you apples falling from trees, but I can’t show you the theory of gravity! I can show you a picture of a strawberry, but I can’t describe your experience of the taste of a strawberry. It’s the same when we see a great hit in a bout. We are seeing the deployment of a technique, but we are not experiencing the fencer’s feeling for the moment.

How you see fencing and your interpretation of reality will always be relative to your own experience, culture, language and perspective. How else can it be? Afterall, we know what we know and don’t know what we don’t know. So in order to make this work I’m going to ask you to suspend your own reality for a while, like sitting down to a good Sci-Fi movie and take a journey with me from my perspective. This journey is about finding ways for fencers to develop skills that allow them to move and adapt as if by some alchemy to micro-changes in distance and cadence and with a laser sharp feeling for time-to-contact at speeds that defy our understanding.

What I have discovered on my journey is that everyone already has these perceptual skills and that trying to instruct techniques with a view to developing already fully formed faculties is tantamount to force-feeding them stuff they don’t need, to gain skills they already have.

There’s no need to instruct distance control when we already have this ability inbuilt to our sensory motor systems. What we do need to do is to let these skills adapt to the nature of the environment, to distances where we feel the opponent is hittable or their attack is escapable or counter-able.

A few caveats before I take the plunge.

The CLA doesn’t bring with it any new methods or moves. It’s a methodology, one that is distinguishable from any other because it is based on ideas about adaptation from ecological science, systems behaviour thinking about self-organisation and non-linear learning. The way I was taught to coach was characterised by a large degree of control over the input, processes and outputs towards developing fencing actions. In the CLA, I had to learn to give up that control so that functional adaptation could do its magic. As I work through some examples, you will certainly see steps and lunges, parries, disengages, pris de fers etc. These have been regarded as the fundamentals of the sport for years and thought of as necessary before skill can be built. What I hope you’ll see for yourselves in the following videos is how a non-technical approach to our game is not only possible, but perhaps desirable. Look beyond the actions to the interactions and understand that the CLA practitioner’s intention is to develop the fencer’s perceptual skills, their tactical awareness, sense of distance and a feeling for tempo. These I have come to think of as the essentials of the game.

By coaching the essentials there is always technique, but don’t let that fool you, it’s not about the technique. The techniques that you will see are nothing more than artifacts of the fencer’s perceptual learning and emerging skilfulness.

A final health warning; please try to avoid cut-and-paste of anything you see and read from this point on. In fact if you set out to do this, you’ll find there is nothing here to see, you already know the names of the actions, you already know the input, process and output of how to teach them; there is nothing new to learn. Instead I invite you to try to get inside my head, the reasons behind the decisions I make, the coaching intention, the individual focus and how all of that links to the CLA framework.

The problem you’ll run into otherwise is demonstrated in this first video. In the course of moving up and down the piste, the fencer sets up the point-in-line (PiL) when he feels it is relevant. I am acting representatively so for example if it is set up too late I’ll just hit him. Even before the action, the way the interaction is formed must be relevant and specifying and if I’m afforded any opportunity to defeat it, I will. To do otherwise would be to do a disservice to the fencer’s skill development. The fencer can use any footwork or technique he likes to set it up, I use beats, pris de fer, engagements, direct hits to his wrist etc etc. With this amount of variability, his attention is on the game, no single action. In fact, this fencer has no clue what a pris de fer is, or as transpires, what a first counter riposte is! I was playing as representatively as I can and I found a little challenge point towards the end of the session where I could draw his PiL and I did so to make a counter action on it.

Now have a look at this comment made under the post.

“Is this a first counter-riposte? That is, the fencer on the left attacks knowing that they will be parried, but once parried, they draw the riposte which they then parry, and finally riposte and get the point?”

This is a typical old-school reductionist action-based turn-by-turn script for what is going on and it is entirely insufficient to explain the skill that is being exhibited here. This sort of technical analysis can easily lead the coach to believe that in order to achieve this skill, you have to teach the actions as described. A logical fallacy! You can certainly rely on descriptions of fundamental actions to describe positions, but positions are not fencing: positions don’t work as a useful descriptor of motion, of relational play.

The performance situation is unscripted, messy and chaotic and there is no time for decision making about individual techniques, only acting decisively in unique interactions. By training fencers to embrace the chaos, we are coaching their attention on the essentials and away from the fundamentals, from technique-fulness to skilfulness. Skill acquisition is all about skill transfer and the CLA is designed to ensure a high likelihood of transfer into the bout.

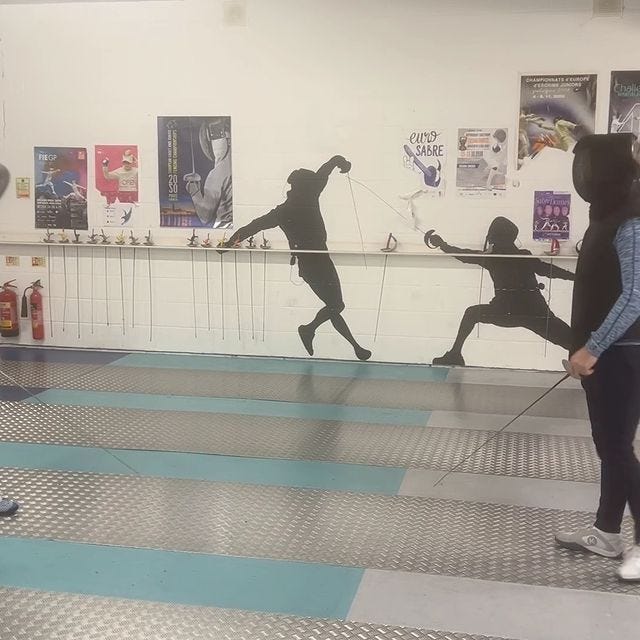

All of those caveats being made, let me now take you on a short journey with some very typical fencers aged from 6 through to 16 and to highlight some of the elements of the CLA framework as we go. To start with, here are some fencers who have never fenced before. I get them to explore moving up and down the piste without running. They get to appreciate the space, the dimensions of the piste and how they can manoeuvre their limbs. They put the obstacles on the floor where they want them to go, so from the very start the idea of co-design and autonomy is a feature. I encourage but stay away from instructing, it’s too tempting to jump in and tell them what to do, I mean, it just doesn’t look anything like fencing, right?

After a few minutes we start to look at preparations in the 4m. I use the word “step” - I consider that a potential error on my part. I don’t want them to get wedded to ideas of technique, I need them to move, not to think about a move - I don’t even want them to know that there is a move! The game will sort all of that out; more on this in a bit. I think I get away with it, otherwise you’d get them overly concerned and internalising an idea of a thing that has a value and can be done correctly or non correctly. You’d see a stiffening in their movement as they try to do what they think the coach wants them to do.

After about 15 minutes into their fencing career we are getting some good movement, but also some unhelpful behaviour that is outside any relevance to the game. In systems thinking there is the idea of the uncontrolled manifold, so don’t let anyone tell you that all variability is good variability, that any constraint will cause good change, or that there is no role for the coach (common misinterpretations of the CLA). The boundaries constraining game behaviours are the dimensions of the piste, the rules of the game and the principles of play. Together they are used to guide or scaffold their exploration and discovery so that they are able to self organise around relevant and representative affordances that contain the essence of the game. Notice how they get a nudge towards the game idea that they are not the attacker after an attack (developing tactical sense of right-of-way). Also I take the opportunity to introduce the idea of indirect ripostes.

So after about 30 minutes work, this is beginning to look like something that will let them play and develop within the rules of the game.

And here’s Owen, just 6 yrs old, having gone through similar process and his first go on electrics. He’s been fencing for less than an hour and demonstrates here a fabulous attaque-au-fer. What a star!

By session 3 we are getting good movement and gamesense. Nice stop hit!

“Dogs bark at things they don’t understand.” Heraclitus

So what about technique? Surely none of this can work in the real world of fencing? None of these CLA types will ever get results! Comments I’m seeing and hearing a lot on social media at the moment. Well as you have seen above, there is always technique when they play. It might not yet be to your taste, but it is functional within the limits of their appreciation of this new space and new game. At this age and stage, technique is meaningless outside of a game context and I want to keep it that way, I believe that is a good thing. During a bout, where do we want their attention to be focussed? On the quality of single steps and arm before foot, or on an understanding of the game? In this approach we are teaching game first and allowing the technique to emerge. It’s an idea that sets the dogs barking, it is so outside of our experience of fencing coaching.

Here is a very small snippet of a game that develops a focus on point control. Very simple. Put the point on your opponent’s mask before they can put theirs on your mask. Referee and score this game as if it was a real bout and you’ll see functional awareness of the point arise in seconds. Neither of these fencers had ever fenced before this session. All that was needed next was a new “rule” that they had to hit the mask before the other player AND before their front shoe lands and you’ve pretty much got a nice fast point-led in-time direct attack and an idea that the attack is over in sabre when the front foot lands (note that I use the word shoe rather than foot to maintain an external focus).

There are plenty of people out there who will tell you what is “allowed” in CLA and what isn’t, but that’s a bit weird, the CLA is an ecological way of thinking and from that viewpoint nothing is excluded and everything has the potential to influence everything. For example, there is no reason to exclude technical instruction and drills if you think it is relevant. Actions without the need for perception/problem solving in game-like situations probably isn’t skill acquisition though. But neither is leaving the kids with a bag of equipment and getting them to work out that they need to put on masks first! No coaching methods are excluded, it will very much depend on the coaching intention. Here’s a neat exercise that I use to demonstrate the difference between a technique, a drill and a skill - by including them all in one exercise! The set up is important and as the fencers get a feel for how to move together they are certainly practicing the step, lunge and step-lunge collaboratively and in doing so they create the conditions for the game which is very simple - to hit with a flunge whilst your opponent is doing everything they can to make you fall short after a failed attack. Toby makes it look easy, but it can get quite spicy once the fencers get competitive.

https://www.instagram.com/tv/CYo2eMrvopa/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Since taking up a games/CLA approach to coaching in 2017 I haven’t found anything that can’t be taught in the context of the game/scaled version of the game or in a game-within-a-game. I have found though found many limitations to teaching isolated techniques and drills, such that today I’d challenge anyone who feels that skill can be developed outside of the performance context.

The alternative from the cognitive view of coaching is that we should teach technique first and then teach it again in a game context. How else do they know what to do? I have a different question, why separate the perception from the action and in effect have to teach fencing twice? Regardless of which theoretical view you take, the evidence strongly suggests that training the perception and action systems of the body together and in context is essential to developing skilfulness. Even for beginner fencers, the need for relevant (representative) and specifying cues creates a feel for the essential game elements and takes them away from attending to the correctness of fundamentals.

Here’s another example where I get fencers to coach each other to attend to perceptual cues. You’ll also see here that I’ve constrained their movement with some equipment on the floor, together with a basic problem being presented by a partner.

And after this excellent coaching you’ve just seen from 9yr old Ethan, Harry goes on to win the British Championships using these very same game essentials.

Here’s a couple of variations of games to help teach the skill of gaming each other in the middle in sabre. In the first one, if you keep hold of the ball and go through the middle you keep right of way and win the game.

And then there is this one. If I remember correctly, something was broken in the other room whilst playing dodge ball and these boys were hanging around as we were reaching for brooms to sweep up. So I just got them onto the piste and played…

If I do feel the need to explore an isolated technique, then I can always find a game to convey it. Here’s one that we use for teaching the stop hit that I picked up in Russia. The important point here is that both fencers have equal and competing roles. One has to attack whenever they like and make a positive effort to score, the other has to take the stop hit and escape without being hit.

Again this translates very nicely into the performance situation.

But remember, on this journey it’s never about the action, seductive as that might be. When training using the CLA framework, the form of the action is a secondary consideration to tuning the fencer in to the tactical-distance-timing context at any moment. It’s not so much about what a coach might specify as desirable “if they do x you do y” and more about how they inhabit the game and it is how the game unfolds that defines what is relevant and how the two fencer’s capabilities determine what is possible.

In fencing there are only three techniques: hit them first, take their blade and hit them, make them miss and hit them. Once we accept that, we can now attend to the tuning up of their percpetion-action skills in the context of realistic scenario training.

Here’s an interesting one. What do you think this game is doing?

Answer: the coaching intention here is actually not to teach defence, but to teach the attacker how to make their opponent parry where they want. In the next video, I show how that idea is developed. The fencer is encouraged to prepare however they want and to sense when to go. The emphasis is on the tactical-distance-timing interdependency, not on any specific action. Note that the attack tempo is also sending my parry to the wrong place and I search for challenge point work opportunities on the fencer’s final tempo i.e. see how at the end of the attack the fencer does not know the nature of the defensive relationship, it’s not scripted. In this way I ensure that he is not doing things, rather he is playing the game.

And again, here is the transfer into competition, with Miller in his first year at U20 winning the British U20 Championships last weekend.

We can constrain the fencer and the fencing in many ways. The important thing is the coaching intention. In this extreme example the fencer is exploring defending the middle, moving the point through distance and dealing with a variety of opportunities to defend as afforded. Weird though, right? But sometimes it’s good to examine the nature of the game from different perspectives and by adding in random and weird, changing things up, perturbing the system. Not for the faint hearted this particular example: Kate is hyper-mobile and has very unique anthropometrics!

Lastly I just wanted to try to demonstrate how skill acquisition is not technical acquisition. Through representative practice and self-organisation the CLA is primarily concerned with the emergence and transfer of skill into performance. Skill in this context is about functional adaptation, something quite different to remembering, repeating, rehearsing and recalling actions. In this clip, I’ve given the fencer the constraint of making a preparation by hopping with their backfoot, so no step and it is designed to keep him in the air and in motion. This particular fencer over-thinks, self-doubts and it gets in the way of his perception-action. I mention this to highlight the uniqueness of the coaching decision in relation to this individual’s needs at this particular time. The problem to be solved is to couple his perception and action and to prevent him stopping to think and judge his execution of any particular part of the interaction. You’ll see a hint of that over-thinking in the final flunge action, but I think these kind of exercises will be good for this fencer to get him to explore more with commitment and hopefully with a smile!

This very exercise was transfered to good effect at last weekend’s British Cadet Championships by Josh on his way to winning the title. It’s the same principle, same game, but note the gamesense, variation, power and commitment.

Concluding Comments

Last week I was shown some social media comments to the effect that no CLA practitioners will ever be able to achieve results. So I hope you’ll forgive my references to results in this blog, they are deliberate even if they make me feel uncomfortable. I’m usually very careful to avoid or to encourage outcome bias. For me success is a poor indicator of the reasons for success, a shallow pursuit and one that often detracts from more useful evolving conversations and reflections on theory and practice. What I would say is that the results the fencers coached using CLA are achieving are very different in depth and quality to what I’ve seen before. With silver to a final year cadet and gold to a first year under 20 at the British U20 Championships, they did look impressive and able to hold their own with the rest of the GB U20 squad. These are very very early days for CLA in fencing and as I’ve said many times, this is no moment to declare victory. I feel through a lot of hard collaborative work, we have just about got to the start line by having worked hard to gain an understanding of the framework and how it might relate to fencing. What cannot be said though, and it is my only point here, is that the CLA does not produce results.

What I hoped to do in this article was to showcase the CLA and how it might operate over the lifetime of fencers in these examples between the ages of 6 and 16 and how this is possible with a non technical-tactical methodology. The key principles of representativeness, guided discovery, self-organisation, non-linear teaching and emergent learning outcomes are the areas I hope I’ve been able to demonstrate. As I said at the beginning, you can take any of these exercises and replicate them via technical instruction, but that would be to miss the point of the coaching that is geared towards the individual’s perceptual learning of what fencing is, how to move in the fencing habitat and elevating their ability to adapt to change and to act decisively in the context of the game.

Many thanks for taking the time to read this article. Feedback is a gift, please let me know what you think.

A few months ago our beloved daughter Victoria died. She would have had her 30th birthday this month. She was much loved in the fencing community and had been instrumental in setting up programmes that have introduced thousands of children to our sport. If you would like to subscribe to this newsletter please know that all proceeds go directly to developing grassroots fencing in Scotland. Many thanks for your support and for all your hard work and contributions to our amazing sport.